Hats, War, and the Great Peace

Three hundred and eighteen years ago this month thirty-nine tribes of native peoples and the government of New France signed The Great Peace of Montreal ending almost a century of bitter warfare. It was a stunning accomplishment…but I’m getting ahead. It began with a hat.

In the fourteenth century, Chaucer described a felted beaver hat in the Canterbury Tales telling his readers the merchant wore “Upon his head a Flandrish beaver hat,” one imported from Flanders, there being no English hat trade at that time.

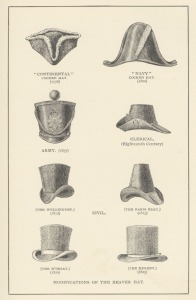

England began importing beaver pelts for hats from Russia a hundred years later. Felted beaver fur, warm, soft and easily shaped, increasingly became the preferred hat material. By 1550 the fashion for beaver hats was all the rage, and remained so for three hundred years.

England began importing beaver pelts for hats from Russia a hundred years later. Felted beaver fur, warm, soft and easily shaped, increasingly became the preferred hat material. By 1550 the fashion for beaver hats was all the rage, and remained so for three hundred years.

By 1600 beavers had been hunted to extinction in Europe, giving incentive to the enterprising merchants who began trading for beaver along the coast of North America. By 1540 in fact, French ships traded goods for beaver pelts at the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River. The hats and the beavers lead us to the Iroquois League and their traditional rivals, the Algonquin speaking peoples of Canada. As luck—good for some, less so for First Nations and the beaver—would have it, European colonization of North America was about to begin. Gold and silver failing to appear in great abundance, European hunger for the next great valuable, beaver pelts, provided a strong incentive to the more adventurous.

Fighting of some sort (it has been characterized as a blood feud) occurred among the various peoples of the Saint Lawrence Valley between those early contacts and the permanent arrival of the French in 1601. It is tempting to think competition for beaver contributed, but we don’t know. What is certain is that Samuel Champlain was approached by a group of Algonquin speaking tribes including the Huron and Montagnais for help as soon as he and European military weapons arrived. By 1603 an alliance of sorts against the Iroquois had been created.

In the first decades of the new century Champlain and his Huron and other allies defeated the Iroquois repeatedly. At the same time the trade in beaver pelts prospered. Competition arrived soon enough, however, in the form of Dutch traders moving up the Hudson River to establish trading posts in what is now upstate New York. Unlike the French they were happy to trade firearms, and the Iroquois began to rely on the beaver trade as a source for western guns. The English followed and their policies were similar. However the French continued to dominate the trade, expanding down the Saint Lawrence, the Ottawa, the Mississippi and the Great Lakes.

The stage was set for what is became known as the Beaver Wars. While the French continued to refuse to trade for arms, by 1630 the Iroquois were fully armed through their relationship with the Dutch and had a near monopoly of the fur trade in the Dutch posts. At the same time the beaver populations began to decline, forcing trappers and hunters to seek new sources. By 1640 competition for hunting grounds and trade routes broke out into open war with the Susquehannock allying with the Huron, and the rival Iroquois nations dropping traditional rivalry in favor of a stronger confederation. Attempts at peace failed.

For the fifty years that followed, war raged intermittently, alliances formed and reformed. The list of tribes, massacres, battles, and alliances would over whelm this short article. Throughout, the Iroquois stood out as the strongest single culture Their raids on French settlers took on almost mythic status. The Dutch armed the Iroquois directly and the English traded arms to them. The French, viewing them as dupes of the Protestant powers, refused to trade with them, their exceptions being the Catholic Mohawks who settled near Montreal.

For the fifty years that followed, war raged intermittently, alliances formed and reformed. The list of tribes, massacres, battles, and alliances would over whelm this short article. Throughout, the Iroquois stood out as the strongest single culture Their raids on French settlers took on almost mythic status. The Dutch armed the Iroquois directly and the English traded arms to them. The French, viewing them as dupes of the Protestant powers, refused to trade with them, their exceptions being the Catholic Mohawks who settled near Montreal.

[LEFT: A page from the Codex Canadensis, circa 1700. 28=a Huron cabin 30=an Iroquis cabin displaying the heads of his enemy 32=a man carrying beaver pelts]

Meanwhile, courtiers at Versailles decorated smaller crowned, extravagantly wide brimmed hats with ostrich feathers and jewels. Similar fashion dominated the court of the Stuarts. The puritans not surprisingly chose plainer head gear, higher in the crown and narrow in the brim, though Oliver Cromwell himself is generally pictured hatless—probably a reaction to the excesses of the cavaliers.

The need for beaver grew and North American was happy to meet that need. The fact that high quality pelts are available only where winters are severe, had given France an advantage to this point. However, by 1670 England had set up competing trading posts fanning out from Hudson’s Bay. In fact supply from North American created a great expansion in hat production in both England and France. By the end of the century, the fashion of pushing up the brim on three sides became ubiquitous, and all classes of people wore beaver hats. The need for pelts continued.

The need for beaver grew and North American was happy to meet that need. The fact that high quality pelts are available only where winters are severe, had given France an advantage to this point. However, by 1670 England had set up competing trading posts fanning out from Hudson’s Bay. In fact supply from North American created a great expansion in hat production in both England and France. By the end of the century, the fashion of pushing up the brim on three sides became ubiquitous, and all classes of people wore beaver hats. The need for pelts continued.

European politics impacted the frontier in a variety of ways. When England deposed James II in favor of his Protestant daughter in 1688, King William’s War offered an excuse for attempts to expand control in North America. In 1689 the Iroquois conducted a particularly notorious raid against Lachine, near Montreal on behalf of the English. French troops accompanied their allies in retaliatory raids, many of which resulted in the carrying off of English captives. England, preoccupied in Europe, provided less support to their Iroquois allies in this period and as the decade progressed the Iroquois were greatly weakened by disease and losses. When England and France made peace in 1697, Quebec and the Iroquois were still at war.

By most accounts all parties were weary after a century of war. The Iroquois, greatly weakened, wanted a bigger piece of the trade and France wanted the fewest possible interruptions to it. There were attempts at negotiate as early as 1690. The colonial French government seems to have seen a window to bring the Iroquois into their alliances to the benefit of the beaver trade. A temporary drop in prices may have provided a further incentive. What followed is remarkable.

In the summer of 1701 13,000 individuals representing thirty-nine distinctive tribal groups descended on Montreal for several weeks of negotiations conducted according to native peoples customs. It didn’t go entirely well. Many distrusted one another; most distrusted the Iroquois. One of the expected outcomes was an exchange of prisoners. The Huron-Wendat Grand Chief, Kondiaronk from territories in northern Michigan, who was one of the architects of the agreement, accused the Iroquois of cheating, at least on the issue of prisoner exchange.

Kondiaronk, however, gave an impassioned speech about the necessity of the treaty that is credited with the final success of the agreement. He died hours later and the governor, Louis-Hector de Callière himself organized a full Catholic funeral with all honors at the Cathedral de Notre Dame in Montreal.

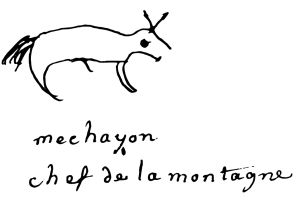

The treaty was concluded the next day with representatives of each nation signing with their clan’s symbol. many of the statements were preserved and make interesting reading. What followed was a banquet, the passing of the pipe of peace, and, of course, more speeches.

To quote just one example, one of the final statements is from the representative of The People of the Mountain. It reads, “You have assembled here, our father, all of the nations to make a mound of axes and to put them in the earth along with yours. For myself, who did not have another one, I rejoice in what you are doing today, and I invite the Iroquois to see us as their brothers.”

The Iroquois representative in turn who spoke, “in the name of the 4 Iroquois Nations, Onondagas, Senecas, Cayugas and Oneida…” claimed they cooperated when others didn’t. (It is important to note that one other Iroquois nation, the Mohawk, were not party to the treaty.) However, he concludes, addressing Governor de Callière, “I request you, Father, to take the hatchet out of their hands so that they may strike no more; if I do not defend myself, it is not for want of courage, but because I wish to obey you.”

This astonishing document is remarkable in its scope and in how well it worked. It has been called “the treaty that established the invaders’ right to live here.” It is still considered valid by many Canadian First Nations but not all. Respected on all sides, it kept peace for over fifty years, enabled the all parties to focus on the fur trade, and facilitated French expansion across the Great Lakes from Detroit to Minnesota and down the Mississippi. Cadillac actually departed for “the straits” to build For Pontchartrain at Detroit during the negotiations. Eventually rivalries between France and England boiled over in what Americans call the French and Indian War and others the Seven Year War. That one cost France deeply, but it is a story for another day.

What drives men to war? Rivalry, greed, economic necessity, territorial ambition, and in some cases, hats.

The mythology of frontier warfare has fueled American historical fiction for generations. Here are a few:

For more in-depth information:

Details about the marks and attendees are here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Peace_of_Montreal

“1701 Great Peace of Montreal,” Mohawk Nation News, June 28, 2012. http://mohawknationnews.com/blog/2012/06/28/1701-great-peace-of-montreal/

“Beaver Wars,” on Military Wikia, https://military.wikia.org/wiki/Beaver_Wars

Carlos, Anne M. and Frank D. Lewis. “The Economic History of the Fur Trade: 1670 to 1870,” on EH.net, the Economic History Association, https://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-economic-history-of-the-fur-trade-1670-to-1870/

Feinstein, Kelly; “Fashionable Felted Fur/A brief History of the Beaver Trade, “History Department UC Santa Cruz, March 2006 https://humwp.ucsc.edu/cwh/feinstein/A%20brief%20history%20of%20the%20beaver%20trade.html

Havard, Gilles, The Great Peace of Montreal of 1701: French-native Diplomacy in the Seventeenth Century, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001

Jaenen, Cornelius J., “The Great Peace of Montreal 1701,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, December 2013. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/peace-of-montreal-1701

“The Great Peace of Montreal,” Pointe-À- Callière/Montreal Museum of History and Archaeology, Teachers’ Centre,

http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/edu/ViewLoitCollection.do?method=preview&lang=EN&id=24707

Caroline Warfield who loves history and all things historical, continues to write historical romance and family sagas covering the late Georgian, Regency, and Victorian periods. Her novel, Christmas Hope is a different turn, a story in four parts each ending on Christmas 1916, 17, 18, 19. It takes place in and around Amiens and northern France into a full length novel, and is currently available for pre-order pending an October release.

Caroline Warfield who loves history and all things historical, continues to write historical romance and family sagas covering the late Georgian, Regency, and Victorian periods. Her novel, Christmas Hope is a different turn, a story in four parts each ending on Christmas 1916, 17, 18, 19. It takes place in and around Amiens and northern France into a full length novel, and is currently available for pre-order pending an October release.

You can find her here: https://www.carolinewarfield.com/

The rise then fall of the beaver pelt market is the catalyst for the “nutria” rat of South America to be imported to Louisiana. Once the market fell out, the nutria became liberated which have been destroying the wetlands here ever since. https://www.louisianafur.com/nutria.html

Save our wetlands, eat/wear more nutria

LikeLike

We’re all part of a single web in this world, I think. When a courtier put on a hat in Paris, he influence an Ojibwe boy in upper Michigan, and the people of Louisiana as well. We can’t be narrow in our thinking.

LikeLike

Can you please expand your comment? As I gave a citation on how the rise and fall of the beaver pelt market and it’s affects still being felt today. I fail to see how that is “narrow thinking”.

LikeLike

By “Narrow” I meant in focus. If we step back—then and now—and look at the web of interconnections we see things like the nutria. Your comment is exactly the opposite of narrow. You are looking at the broad chain of consequences.

LikeLike

Pingback: Running as Fast as I Can - Caroline Warfield