The Federal Reburial Program

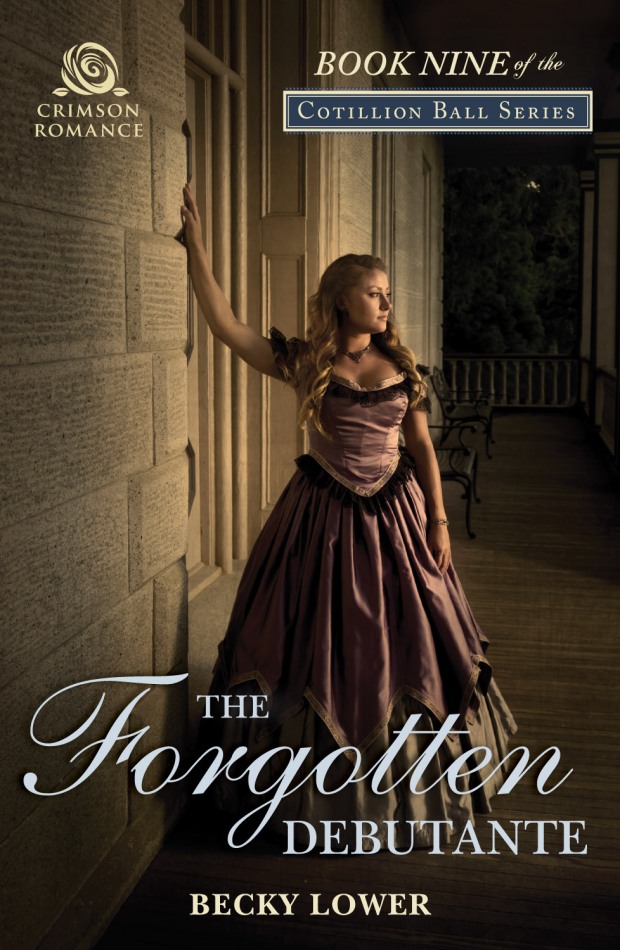

The final book in my Cotillion Ball series, The Forgotten Debutante, is set for release on April 4. The timeline for the entire series is set in America from 1855 through1866. Each of these books focused on an event in American history, from the introduction of the debutante ball phenomenon to the Pony Express, abolition to the Civil War. As I was planning each of these nine books, I unearthed some interesting facts that didn’t make it into the history books. One of these facts is front and center in this last book–the Federal Reburial Program, which involved digging up the bodies of Union soldiers at each battlefield and reburying them in national cemeteries.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress. Work teams with the Federal Reburial Program at the Cold Harbor battlefield.

This program fit neatly into my final story, since I had to face the Civil War in these last two books, but had no interest in heading to the battlefields. It had been done many times over, and quite well, by others. What interested me was how the war affected the lives of everyday citizens who were still trying to live their lives when the war was all encompassing.

Like most Americans who grew up in the eastern half of the country, my summer vacations usually involved visiting one Civil War battlefield after another. We’d pose with the requisite cannon, have lunch in the bucolic fields, and listen with half an ear to the docent relaying information about the battles. Most of the grounds had some kind of cemetery, and we gave no thought to how the men got buried in such neat, orderly rows on the hills of Gettysburg or Manassas or how so many bodies from the Civil War ended up in Arlington National Cemetery.

This massive and grisly undertaking was begun by Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross. She collected tidbits for years on missing soldiers, and formed a clearing-house of information for the desperate families trying to track down their loved ones. She sent out a call asking for any knowledge people had on the missing soldiers. The Sanitary Commission in New York performed a similar service, logging the names and addresses of those soldiers who were in the various military hospitals. But it was not until war’s end that the government got behind these initiatives.

In the fall of 1865, Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs made it his mission as well to find the untended bodies of the soldiers spread across the southern states, where most of the fighting took place. The response to broadsheets asking for information was staggering. Combined with information compiled by both the Sanitary Commission and Clara Barton, the government began to map out each battlefield for graves. Some of the information was extremely explicit on where the bodies could be found. Some of it was rather vague, as you can imagine. Bodies could be claimed by relatives of the deceased, or placed in national cemeteries.

Monument to Clara Barton at Andersonville Prison, erected in 1915. Photo credit: NPS/Eric Leonard

This hard and heartbreaking undertaking took six years, covered thousands of sites, and, in the end, nearly 450,000 bodies of Union soldiers were uncovered and reburied in national cemeteries throughout the north. This project finally put an end to the Civil War.

The Confederate bodies suffered a different fate. The Reburial Program only addressed relocating the bodies of the Union soldiers. Southerners were not a part of the program, even though the bodies of their dead were scattered across the same battlefields. Southern women came to their rescue, not with public funds, but rather with bake sales and other fundraising efforts.

So, the next time you visit a battlefield, or spend time at Arlington National Cemetery watching the changing of the guard at the tomb of the unknown soldier, remember how the bodies of the fallen Civil War soldiers made it into the neat rows of the cemeteries.

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/transcript/death-transcript/

Excerpt from The Forgotten Debutante, when Saffron Fitzpatrick makes it known she wants to be part of the government effort:

“Why don’t you commission Jasmine to make you some new gowns instead? You don’t need to work, Saffron, especially at the Reburial Initiative. We’ll be digging up bodies and bringing them home. You don’t need to be involved in such grisly work. It’s time for you to move on from the war, not get mired in it again.”

Saffron’s hands formed tight fists. This was a battle. Her own war. And she wasn’t about to lose. “I’ve been gathering information on those men who died on the various battlefields for years now. I’m familiar with how to establish files, and I assume the same type of filing system will be put into play in DC. It’s high time I get paid for my efforts after all these years. A new dress isn’t going to appease me this time. I’m no longer a child.”

Halwyn glanced down the table, to his parents. Saffron could read the plea in his eyes for help. This was her one chance, and she had to take it. Her gaze skittered to the end of the table as well, with her eyes filled with a plea of her own.

Charlotte turned to Halwyn. “There’s nothing wrong with Saffron wishing to continue her work. She’s been a huge help at the Commission, and her knowledge will come in handy at the Reburial Program. We were aware the day would come when our youngest would be leaving home.” She turned back to her daughter. “We would not be opposed to your move, Saffron, if Halwyn and Grace agree to it.”

What a great historical tidbit! I love that you’re using it as part of the heroine’s story. I did laugh out loud at the “posing with cannons” line. I’m a native Indianan and I must have dozens of pics of my family at different battlegrounds. The kids always look thrilled (lots of sarcasm there).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Jessica. I’m glad you had the same growing up experiences I did. You wouldn’t think something as grisly as the reburial program would be a good story line, but my heroine viewed it as a giant jigsaw puzzle, which put it into the proper perspective, I think.

LikeLike

The depth of your research amazes me. I never realized about such an undertaking. I had assumed they were buried near the battlefields. Great article.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks,Barb, for taking the time to read about this rather gruesome part of the Civil War. When I first heard about it on one of the history channels, I decided it would be a great way to wrap up the series.

LikeLike

We have a few pictures of my kids posing by cannons. I was amazed at how they managed to get those heavy cannons to the top of mountains. This blog was very interesting. Some of my friends and I were just talking about soldier burial after the Civil War. She and he husband had recently come back from Virginia and toured battlefields and cemeteries. Thank you for posting this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tweeted, commented.

Tina

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Tina. It’s just one of those things you don’t think about, don’t want to think about. But I’m glad there were brave men and women who took care of the grisly chore.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting bit of background that most people never think about. The sad fact is that if the men died somewhere other than a battle field, they were most likely never found. Long dead soldiers from both sides are occasionally uncovered with new excavations, especially in the South.

LikeLike

The entire Civil War was a sad time in our history, and I have no doubt that many were left behind, to never be laid to a proper rest.

LikeLike