George Washington’s Tent

History is made up of people, places, events—and objects. Among the latter Washington’s Marquee (his campaign tent) stands out, if only for its arc of American history.

I first saw the tent at Valley Forge National Historical Park. That the canvas quarters of the great general still existed amazed me, but the inscription in front astonished me. It indicated the tent had been purchased from the daughters of Robert E. Lee, telescoping two great upheavals in American history and dropping it into my lap on a sunny day ninety years later. I have since learned that, like much of American History, it wasn’t that simple.

First of all there were actually at least two pairs of two tents used during the Revolutionary War. Washington used one for a dining room and the other for his office and sleeping quarters. He entertained the officer corps in one, and his staff—secretaries and aides-de-camp including among others, Alexander Hamilton, used the offices in the other. Washington and his enslaved valet slept in the latter.

The first set of two, made a by Philadelphia upholsterer Plunkett Fleeson, was used early in the war through the winter encampment at Valley Forge. The following year a second set was ordered and purchased. It is the second set that survived the war.

After the deaths of George and Martha Washington the tents passed to their grandson, George Washington Parke Custis who, it has been said was prone to giving away bits of them. In any case, the tents were stored at Arlington House in Virginia through the residency of his daughter Mary and her husband, Robert E. Lee.

When the Union army seized Arlington House during the American Civil War, they took the tents as well as other Washington memorabilia. It was an enslaved woman, Selina Gray, who alerted authorities to the importance of artifacts stored there and preserved them from vandalism during that chaotic period. During the following forty years they were displayed or stored variously at the U.S. Patent Office and the Smithsonian Institution. In 1901, President McKinley ordered that they be returned to the Custis-Lee family after they petitioned for the return. The Smithsonian, the National Park Service, and others bought pieces and the tents were split up.

According to a summary in Wikipedia, pieces of the tents are currently owned by four different historical organizations:

- Colonial National Historical Park owns the interior of the dining tent roof, the office/sleeping tent interior, and the poles of the office/sleeping tent. All of these items are currently on display at the Yorktown Battlefield Visitor Center.

- The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association owns the linen door to the office/sleeping tent.

- The Museum of the American Revolution owns the exterior of the office/sleeping tent, poles of the dining tent, and a storage trunk.

In 1909 Rev. W. Herbert Burk purchased the office tent from Mary Custis Lee, daughter of Robert E. Lee on behalf of what was then the Valley Forge Museum of American History. She sold the tent to Burk for $5,000 to raise funds for Confederate widows. There is no small irony that a tent in which Washington slept with his enslaved valet was sold to benefit the widows of the defenders of slavery.

Watercolor depicting the tent by Pierre Charles L’Enfant 1782, owned by the Museum of the American Revolution

That is the tent I saw years ago, the one that now resides in the Museum of the American Revolution in downtown Philadelphia, which opened in 2017 with the tent, displayed behind glass, as one of its centerpieces. The museum, recipient of numerous awards, is a gem. It successfully avoids spoon-feeding visitors myths in favor of showing the revolution and its underlying causes in all their complexity, rather like Washington’s tent. Its displays attempt to cover events from the point of view of the enslaved, the native peoples, and all the classes and segments of society—patriots, loyalists, and even the Hessians who came as mercenaries and stayed, and the Oneida who were dragged into the fight. Everyone who goes comes away thinking, “Wow, I didn’t know that.”

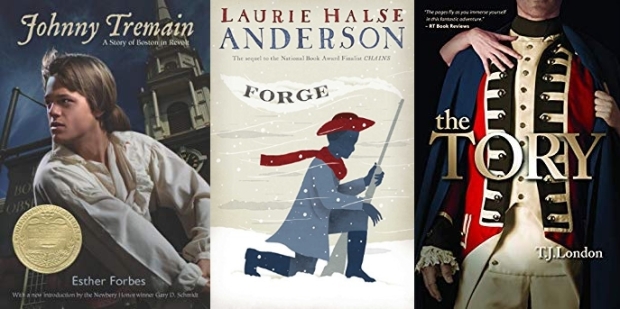

This holiday week when we celebrate our independence is a good week for exploring museums that preserve our knowledge of that time. It also puts me in mind of good historical fiction, which can hold to the facts of an event while telling us the greater truths behind it. Some of my favorites are displayed here. As a good starting point I recommend Laurie Halse Anderson’s Seeds of American series.

For more information I suggest:

Davis, Paul “Surviving the Civil War” first of a three part series on the journey of the tent, on M*AR, the website of the Museum of the American Revolution, https://www.amrevmuseum.org/updates/stories/surviving-civil-war

Gilmore, Kimberly, “George Washington’s Tent: The First Oval Office,” on History, April 19, 2017. https://www.history.com/news/george-washingtons-tent-the-first-oval-office

Marshall, Andrea, “George Washington’s Marquee Tent,” on The George Washington Digital Encyclopedia, George Washington’s Mount Vernon. https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/george-washingtons-marquee-tent/

Caroline Warfield is a writer of historical romance and family sagas covering the late Georgian, Regency, and Victorian periods. She is currently expanding her novellas “Roses in Picardy” and “The Last Post,” which take place in and around Amiens in 1916 and 1919, into a full length novel, Christmas Hope, to be published in mid-October.

You can find her here: https://www.carolinewarfield.com/

I’m putting the Museum of the Revolutionary War on my bucket list!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Do, Becky. It is a must see.

LikeLike

Wonderful and edifying post, Caroline!! Just imagine! A canvas tent has survived three wars on our soil and the vagaries of government agencies. I am so glad it finally has a permanent, protective display area. The museum is definitely on my bucket list!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amazing post, thank you! I hope I get back to philly to see that museum sometime.

LikeLike