Christmas Pusan, 1950

On December 25, 1950, General Edward Almond arrived in Pusan, South Korea along with the very last of the refugees from Hungnam in the north following a horrific military disaster. Chinese forces pushed south of the 38th parallel the same day, invading South Korean territory. That Christmas and the weeks leading up to it impacted my family for decades.

The word “Christmas” brings to mind warm family times, bright lights, and festive decorations. Most of us know that sometimes—particularly in some families—the bright lights dim and people struggle. In the house in which I grew up there was a shadow over the holidays. It set in at Thanksgiving and covered our efforts all the way to Christmas. My father became morose—even more silent, brooding, and bad tempered than usual. As a child I didn’t understand why.

The answer, when I found it, was Korea. The more I learned, the more I understood. First, a short overview of that frequently forgotten piece of American history. My father landed at Inchon, Korea, with the X Corps in September 1950 as a thirty-year old professional solider leading an artillery battery of much younger men. One of them later told me he was alive because Dad taught them how to survive. The operation was ostensibly a United Nations police action to defend South Korea from northern aggression which had driven them to a perimeter around the city of Pusan in the southernmost part of the country, but McArthur, for one, hoped to liberate the entire peninsula from communism.

The early weeks were so successful that the UN forces pushed north, dividing into two groups with the X Corps moving up the west of the Korean peninsula in a drive to the Yalu River, the border between Korea and China. The short history is that the Chinese poured across the border, and trapped the 1st Marine Division on the Chosin (Changjin) Reservoir, with the 7th Infantry Division coming to their aid. A massive retreat ensued in which some units had to fight their way out, with the X Corps and hundreds of thousands of civilians being evacuated from the port of Hungnam. Conditions were hellish with temperatures thirty degrees and more below zero and treacherous mountain roads built for ox carts, not armored vehicles. The details are horrific, and available elsewhere. This article will focus on those that impacted my father—and ultimately the Christmases of my childhood.

According to Dad, his battery reached a ridge above the Yalu, where they looked down on China, unpacked, and set up. They were, he said, ordered to pull out an hour later. I found that elements of the X Corps actually began to face resistance on November 18th as they approached the border. Dad always said McArthur was telling people the Chinese wouldn’t enter the war, but they were already “passing them on the road.” The 7th infantry division reached the Yalu on November 21, although it seems likely (given the terrain and logistics difficulty) that they didn’t all make it the same day. The Chinese crossed the Yalu in force on November 25. Dad’s memory falls somewhere between the two, give or take a day of Thanksgiving, which occurred that year on November 23rd.

The 7th infantry division, which included the 31st and 32nd infantry regiments and artillery units of which  Dad’s 48th FA was one, had been spread thin across the mountain roads. They had to withdraw pulling heavy equipment down one-lane dirt roads, with often a wall on one side and a sharp drop-off on the other. Dad never described trucks going over, but our mother said he witnessed it happening.

Dad’s 48th FA was one, had been spread thin across the mountain roads. They had to withdraw pulling heavy equipment down one-lane dirt roads, with often a wall on one side and a sharp drop-off on the other. Dad never described trucks going over, but our mother said he witnessed it happening.

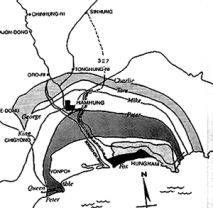

They regrouped south of Chosin to cover the even more horrific retreat of the 1st Marine Division off the reservoir, a march that took 10-15 days and included the almost miraculous reconstruction of a bridge at the Funchilin Pass, which had to be airlifted and dropped into place. Dad told us his gun crew set up at Oro-Ri, holding off the Chinese for the Marines to come through.

Dad described only holding their ground at Oro-Ri and withdrawing to guard the perimeter of Hungnam. I found reference to multiple lines of defensive perimeters that were gradually breached and pushed back to Hungnam. I couldn’t verify the details, but the artillery definitely withdrew in stages to protect the port of Hungnam to give the navy time to evacuate first the 1st Marine Division and then the infantry. The Marines boarded ships December 15.

According to our father, the artillery units were among the last out, even after the civilian refugees. The 7th Infantry division left December 21 and the loading of refugees began. Dad also described the blowing up of stores and destruction of the port. If he witnessed the very end, he may not have left Hungnam until Christmas, but I suspect it must have been a day or two before. The evacuees were taken to Pusan, around which the fortified “Pusan perimeter” represented exactly the extent of territory held by the South Korean and UN forces before the Inchon landing.

Heartwarming stories seep out, even during the worst of wars. Humanity—or propaganda—seems to require them. The battlefield chaplain holding services is a stock figure. I’ve read one story about a group of American soldiers invited to attend Mass at a little village inside the Pusan perimeter. I found typed notes from the National Archives describing holiday activities among the troops at Pusan.

The story Dad remembered was quite different, and it occurred on Christmas itself. It is the one story he

liked to tell, almost the only one we heard until late in his life. The mess tent caught fire, and, in Dad’s version of events, he rushed in to save the turkey and burned his hands tossing giant cans of green beans out to save Christmas dinner. He was awarded the Soldier’s Medal for heroism not involving conflict with enemy—not for saving the turkey but for rescuing the men inside that tent.

My uncles told me emphatically that he wasn’t the same when he got back. He had made it from Normandy to Austria in 1944-45 relatively unscathed in body and mind. Not so Korea. It was decades before I learned the term PTSD, but we lived with it from then on.

Nightmares, jumpiness, depression—Dad had most of the typical symptoms. All vehicles made him nervous at first, but the worst of that passed. While he would never fly, he did drive. To the end of his life he was prone to irrational outbursts when anyone else drove, screaming, and banging on the dashboard if we didn’t do exactly what he ordered, or, God forbid, got too close to the edge of the road.

Holidays were particularly hard, but, because he never talked about it, the moods remained a mystery. After my mother died, we were able to get him to open up somewhat, and things came into focus. One year toward the end he came to brunch and sat in sullen silence for a while before looking up at my brother and asking, “Do you know what I was doing at this time on Christmas in 1950?” By then, we did know. Christmas in the house I grew up in owed much to December 1950. We never quite got over it.

For another soldier’s memory of that Christmas, click here. http://www.stripes.com/news/veterans/an-unforgettable-christmas-eve-midnight-mass-during-the-korean-war-1.385850

Harrowing story. On a visit to Washington it was the Korean memorial which most got to me. It’s a forgotten war and yet the casualties were huge.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful post, Caroline. DC is full of memorials to forgotten wars, and to the brave men and women who fought them. We seem to be bent on repeating our mistakes all the time.

LikeLike

What a great factual article.

LikeLike

What a moving and poignant post, Caroline! While war did not play into my parents’ view on Christmas, the Depression certainly did. My mother hated Christmas because of her own childhood memories and because of the poverty she witnessed among her students in rural south Georgia. Many of Greatest Generation were left with scars no one could see, but that affected their whole lives and their children. I’m glad you were able to discover why your dad acted the way he did.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a heartbreaking story. Thank you for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My Uncle told me what it was like for him on Iwo Jima, my father told me how bad it was in Korea.

It is well that war is so terrible — lest we should grow too fond of it.

It’s noteworthy that this saying is attributed to a man that was very good at war.

LikeLike

SOCIAL MEDIA’D

LikeLiked by 1 person